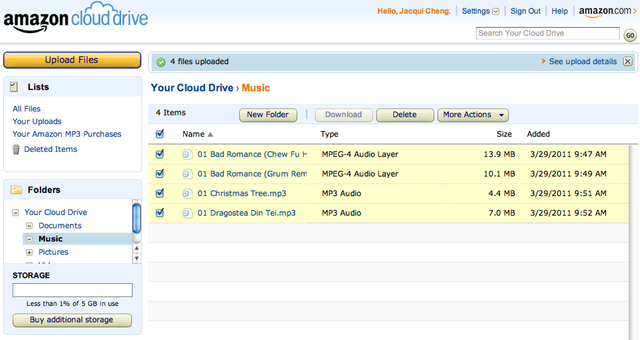

Amazon.com made waves in March when it announced Cloud Player, a new "cloud music" service that allows users to upload their music collections for personal use. It did so without a license agreement, and the major music labels were not amused. Sony Music said it was keeping its "legal options open" as it pressured Amazon to pay up.

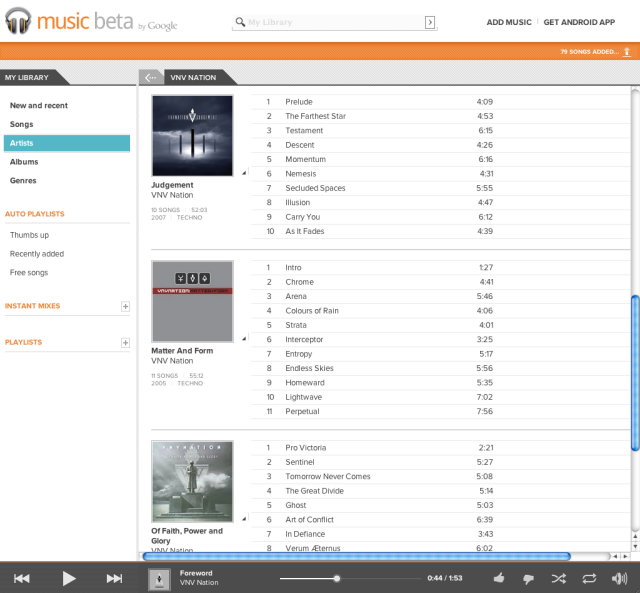

In the following weeks, two more companies announced music services of their own. Google, which has long had a frosty relationship with the labels, followed Amazon's lead; Google Music Beta was announced without the Big Four on board (read our first impressions). But Apple has been negotiating licenses so it can operate iCloud with the labels' blessing.

The different strategies pursued by these firms presents a puzzle. Either Apple wasted millions of dollars on licenses it doesn't need, or Amazon and Google are vulnerable to massive copyright lawsuits. All three are sophisticated firms that employ a small army of lawyers, so it's a bit surprising that they reached such divergent assessments of what the law requires.

So how did it happen? And who's right?

A lost decade

It was a service ahead of its time. Slip a CD into your computer, and the music on it would instantly be added to your online locker. From there, it could be streamed to any Internet-connected computer. Several services do this today, but MP3.com was launched more than a decade ago.

The site was a 1990s dot-com star, flush with cash from its $340 million IPO. The recording industry sued, arguing that MP3.com needed licenses to store and then stream their music. MP3.com countered that the technology was legal under copyright's fair use doctrine, much as format-shifting a CD might be.

A federal judge sided with the labels, and the threat of astronomical statutory damages forced MP3.com to settle the case for $53.4 million. Weakened by litigation and the bursting of the dot-com bubble, the company was forced to sell itself to Vivendi Universal in 2001; the music locker feature was abandoned soon afterwards.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...